Most of our buildings use water, so potential for Legionella in buildings is greater than many think.

Legionella in buildings

Unless you’ve been on vacation all summer, or you’ve been watching my beloved Chicago Cubs have a great season, you’ve heard or read about the Legionnaire’s disease cases in New York City. The 2015 outbreak, traced back to a Bronx hotel cooling tower, has caused 12 deaths and sickened 120 people.

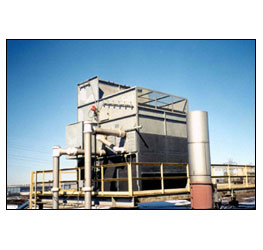

Obviously, this story is newsworthy, but it turns out Legionnaire’s disease can occur anywhere if the right circumstances are present. After all, many of these cases are tied to certain building mechanical systems, like cooling towers and fountains. Let’s see – how many of our buildings have mechanical systems that could be susceptible? Pretty much all of them.

Legionnaire’s cases (or related problems like Pontiac Fever) many times go unreported, which make me wonder about the actual occurrence rate. The takeaway here is any building has the potential for Legionella problems. So if you own or operate a susceptible building, you’re an architect or engineer design new construction or renovations, or contractors, it’s a good idea to see what hazards may be present. And if you’re a program manager (like a real estate portfolio management firm) you may want to pay attention to this also.

I’m thinking about you, your employees working on and around this equipment, and the building occupants. Notice that I haven’t yet mentioned any specific building category. To minimize your risk, I think it’s a good idea to be proactive about potential Legionella problems. This isn’t just a big city problem, or one confined solely to a certain region of the United States.

Obviously for healthcare facilities, Legionella can be a huge problem – patients and staff can be particularly susceptible to various problems, including Legionnaire’s outbreaks. American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE) and The Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) are good resources.

In fact, JCAHO issued a new standard that became effective January 1, 2001. This standard, numbered EC 1.7, requires all JCAHO accredited facilities to have a management program to “reduce the potential for organizational-acquired illness.” It holds the health care facility responsible for “managing pathogenic biological agents in cooling towers, domestic hot water, and other aerosolizing water systems.” My bet is many of you are already aware of this standard and are working to stay (or get) in compliance.

But what about buildings that aren’t healthcare facilities?

The American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) is a great resource. ASHRAE Standard 188-2015 — Legionellosis: Risk Management for Building Water Systems (ANSI Approved) was developed for all building types. From the ASHRAE standard description, “ASHRAE Standard 188 establishes minimum legionellosis risk management requirements for building water systems.Included in this publication are: description of environmental conditions that promote the growth of Legionella and informative annexes and an informative bibliography that contain suggestions, recommendations, and references to additional guidanceIn addition, content throughout the document is revised to bring it in line with current technical standards. Standard 188 is essential for anyone involved in design, construction, installation, commissioning, operation, maintenance, and service of centralized building water systems and components.”

OSHA’s website has considerable information on Legionella – background information, susceptible building systems, assessment, plus links to other websites.

Any building – schools, hospitals, office buildings, hotels, you name it, could have a Legionella problem. I recommend conducting a screening to see where you stand. And if you’ve already completed your assessment, share your tips with others.

If you’re just getting started, here are some steps to take now:

– Assess building systems to determine susceptible components (cooling towers, spas, fountains, potable water, non-potable water).

– Develop a Water Management Program.

– Implement training and Operations and Maintenance Program to minimize Legionella risk.

– Take corrective actions as determined in the assessment and as directed by the Water Management Program.

Just remember, this will take time. And we’re all busy. So if you need help:

Wynn’s a good guy to have around if you like corny jokes and want to solve tricky environmental problems

Please send me your Legionella project experience, and I’ll include your responses in a future post (details kept confidential). If I can help with anything, give me a call (225-761-9141 extension 22) or send me an email at cwhite@wynnwhite.com. Or if you’d like an outline of Legionella assessment criteria and Water Management Program items, email me.

Stay disinfected, my friends.